Obsession with money

Louisa May Alcott wanted money. Lots of it. Her journals and letters leave no doubt on how important money was to her: they are packed with entries about how much she earned, spent, or sent back home to her family.

Louisa May Alcott wanted money. Lots of it. Her journals and letters leave no doubt on how important money was to her: they are packed with entries about how much she earned, spent, or sent back home to her family.

That obsession started when Louisa was very young and she saw her parents, especially her mother, struggle with poverty. Her father never provided for the family, leaving them hungry and with no home of their own, so Louisa decided she would be the one to take care of them.

At ten, she promised herself she would become rich. In her teenage years, she worked any job that came her way (sewing, laundry, cleaning, domestic servant, teaching, writing) and started the habit of recording her income and expenses. She also wrote down jobs, names of her employers, tasks she had to do, how much she liked or disliked them, titles of stories or poems she was paid for, observations on whether her pay was fair or whether it was going up or down. Her handwriting is hard to decipher, her feelings about money are not.

At twenty-five she vowed to “take Fate by the throat and shake a living out of her.” At thirty-five she published Little Women and, for the first time in her life, she had enough money to provide for her family and pay off their many debts. After that, she went on to earn the equivalent of two million dollars in today’s money from the sales of her novels and stories. All income was still carefully recorded, whether it was thousands of dollars for new novels or the $25, $50, or $100 she received for the occasional poem or short story.

At twenty-five she vowed to “take Fate by the throat and shake a living out of her.” At thirty-five she published Little Women and, for the first time in her life, she had enough money to provide for her family and pay off their many debts. After that, she went on to earn the equivalent of two million dollars in today’s money from the sales of her novels and stories. All income was still carefully recorded, whether it was thousands of dollars for new novels or the $25, $50, or $100 she received for the occasional poem or short story.

To her credit, the money obsession didn’t damage her character, but it did make it hard for her to slow down or feel satisfied with what she had already accomplished. In a letter she wrote years after the success of Little Women, she told her older sister that she couldn’t forget the many “weary years of my youth, the work, the waiting and disappointment, and feeling as if the hounds were after me.” For the rest of her life she felt compelled to earn more and continued to “spin her brains for money.”

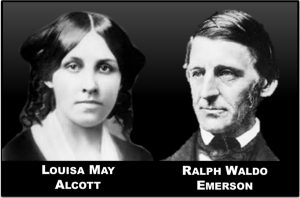

Ralph Waldo Emerson: teenage crush and lifelong admiration

Ralph Waldo Emerson played a big part in Louisa’s life. He was one of the few people who saw both the folly and the goodness of Bronson Alcott, Louisa’s father, and supported Bronson even though he didn’t always agree with him.

Ralph Waldo Emerson played a big part in Louisa’s life. He was one of the few people who saw both the folly and the goodness of Bronson Alcott, Louisa’s father, and supported Bronson even though he didn’t always agree with him.

That made a big impression on young Louisa. She fell in love with Emerson at fifteen, the way Bettine von Arnim fell in love with Goethe. Louisa outgrew her teenage infatuation later but not her feelings of respect, admiration, and, one can argue, love without expectations. Emerson remained “the god of her idolatry” for the rest of her life.

Here are some of Louisa’s own words about Emerson:

My romantic period began at fifteen, when I fell to writing poetry, keeping a heart-journal, and wandering by moonlight instead of sleeping quietly. About that time, in browsing over Mr. Emerson’s library, I found Goethe’s Correspondence with a Child, and at once was fired with a desire to be a Bettine, making my father’s friend my Goethe.

So I wrote letters to him, but never sent them; sat in a tall cherry-tree at mid night, singing to the moon till the owls scared me to bed; left wild flowers on the doorstep of my “Master,” and sung Mignon’s song under his window in very bad German.

Not till many years later did I tell my Goethe of this early romance and the part he played in it. He was much amused, and begged for his letters, kindly saving he felt honored to be so worshiped. The letters were burnt long ago, but Emerson remained my “Master ‘ while he lived, doing more for me, — as for many another, — than he knew, by the simple beauty of his life, the truth and wisdom of his books, the example of a great, good man, untempted and unspoiled by the world which he made better while in it, and left richer and nobler when he went. (from a letter Louisa wrote to a friend)

Father had four talks at Emerson’s. Good people came and he enjoyed them much; made thirty dollars; Emerson probably put in twenty. He has a sweet way of bestowing gifts—on the table, under a book, or behind a candlestick, when he thinks Father wants a little money and no one will help him earn. A true friend is this tender, illustrious man. (from a journal entry in 1860)

Reluctant vegan

Plain boiled rice without any sugar. Graham meals without butter or molasses. Apples and berries or nuts picked up during walks through the country. Those were the meals Louisa May Alcott grew up with because her father believed all animal products were bad for the body and the spirit, and her mother had no money for other kinds of food regardless of what she believed.

A family acquaintance often saved pieces of pie and cake in a bandbox for Louisa and her sisters and gave them to the young girls. Louisa was only a few years old then, but the memories of those culinary delights were strong enough that, many years later, when she was a famous author and met her acquaintance in the streets of Boston, she greeted her with warmth and gratitude.

“Why, I did not think you would remember me!” the old lady told Louisa.

“Do you think I shall ever forget that bandbox?” was the instant reply.

When she was ten, Louisa’s father started a utopian community with even stricter rules about food and drink. Louisa used humor to talk about the new diet in the short story Transcendental Wild Oats.

Unleavened bread, porridge, and water for breakfast; bread, vegetables, and water for dinner; bread, fruit, and water for supper was the bill of fare ordained by the elders. No teapot profaned that sacred stove, no gory steak cried aloud for vengeance from the chaste gridiron; and only a brave woman’s taste, time, and temper were sacrificed on that domestic altar.

Even salt was considered a useless luxury and spice entirely forbidden by these lovers of Spartan simplicity. A ten years’ experience of vegetarian vagaries had been good training for this new freak, and my mother’s sense of the ludicrous supported her through many trying scenes. (Louisa May Alcott – Transcendental Wild Oats)

Louisa disagreed with her father on several issues, and food was one of them. Once she became wealthy, her eating habits changed. She didn’t lose her appreciation for simple meals and talked of times when she ate bread and strawberries, or bread, milk and baked apples. But there were also times when she drank wine and ale, smoke cigars, and ate several-course meals that would have satisfied any carnivore.

In a letter she sent home in 1870, during her second trip to Europe, Louisa wrote the following about the food:

We still dawdle along, getting fat and hearty. The food is excellent. A breakfast of coffee and tip-top bread, fresh butter, with eggs or fried potatoes, at 8; a real French dinner at 1.30, of soup, fish, meat, game, salad, sweet messes, and fruit, with wine; and at 7 cold meat, salad, sauce, tea, and bread and butter. It is grape time now, and for a few cents we get pounds, on which we feast all day at intervals. (from a letter Louisa May Alcott sent her parents in 1870.)

Happily unmarried

Louisa fell in love twice: at fifteen with the unavailable Ralph Waldo Emerson and at thirty-two with the much younger Ladislas Wisinewski. Some biographers argue that she also loved Henry David Thoreau but her feelings for the author of Walden looked more like friendship and admiration which (maybe) contemplated love for a few moments without becoming intense or serious enough to qualify as that.

Louisa fell in love twice: at fifteen with the unavailable Ralph Waldo Emerson and at thirty-two with the much younger Ladislas Wisinewski. Some biographers argue that she also loved Henry David Thoreau but her feelings for the author of Walden looked more like friendship and admiration which (maybe) contemplated love for a few moments without becoming intense or serious enough to qualify as that.

Most marriages she saw, including her parents’, left her with no desire to marry. She was moody and joked that she didn’t want to inflict her moods on a spouse, and, the older she got, the more she valued her independence.

All that contributed to her decision to remain single. For the most part, she enjoyed her “spinsterhood”. If she had any moments of regret they were few and became apparent only when she talked about other people, not about herself.

An example is the words she wrote to her father in 1875 on her forty-third birthday:

I suppose you are thinking of Wilson just now, and his quiet slipping away to the heavenly council chambers where the good senators go. Rather like Sumner’s end, wasn’t it? No wife or children, only men and servants. Wilson was such a genial, friendly soul I should have thought he would have felt the loneliness very much. Hope if he left any last wishes his mates will carry them out faithfully. (from Louisa’s letter to her father)

Remembered with love and respect

Like all families, the Alcotts had many faults. Unlike most families, Louisa’s fame made those faults a highly sought target. Louisa knew that well so, in 1884, she burned many of her old letters because it was “not wise to keep for curious eyes to read and gossip-lovers to print by and by.” Years earlier she had the same thing with her mother’s letters and journals.

Like all families, the Alcotts had many faults. Unlike most families, Louisa’s fame made those faults a highly sought target. Louisa knew that well so, in 1884, she burned many of her old letters because it was “not wise to keep for curious eyes to read and gossip-lovers to print by and by.” Years earlier she had the same thing with her mother’s letters and journals.

In 1885, she was asked to send a few words about herself for a new collection about famous women. She declined and, in a letter to Thomas Niles, her publisher, repeated her wish to be done with the “everlasting notices” about herself.

Dear Mr. Niles, — Thanks for the book which I shall like to read. Please tell Miss N. that she will find in Sanborn’s article in ” St. Nicholas” or Mrs. Moulton’s in the “Eminent Women” book all that I wish to have said about myself. You can add such facts about editions, etc., as you think best. I don’t like these everlasting notices; one is enough, else we poor people feel like squeezed oranges, and nothing is left sacred. George Eliot’s new life and letters is well done, and we are not sorry we have read them. Mr. Cross has been a wise man, and leaves us all our love and respect instead of spoiling them as Froude did for Carlyle, Yours truly, L. M. A. (from a letter Louisa sent to Thomas Niles)

Stage fever

It’s hard to imagine Louisa May Alcott as anything but a writer yet writing was not her only artistic outlet. Acting was too.

It’s hard to imagine Louisa May Alcott as anything but a writer yet writing was not her only artistic outlet. Acting was too.

She started acting from a very young age in plays based on fairy tales and made-up stories. She loved entertaining her family and neighbors and usually played the parts of the villains because they had most dialogue and action. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s son wrote that Louisa could make her audience’s sides ache with laughter with her dramatic skills.

At seventeen, Louisa wrote in her journal about Anna, her older sister, and herself becoming professional actresses. She admired Sarah Siddons and her niece, Fanny Kemble, and wished to be as talented and famous as they were.

Anna wants to be an actress, and so do I. We could make plenty of money perhaps, and it is a very gay life. Mother says we are too young, and must wait. A. acts often splendidly. I like tragic plays, and shall be a Siddons if I can. (from Louisa May Alcott’s journal in 1850)

Louisa listened to her mother and waited. At twenty-five, she had another episode of being “stage struck” and wrote, “Perhaps it is acting, not writing, I ‘m meant for. Nature must have a vent somehow.” Her plans didn’t work out – she decided that, while she had the skills to be a good amateur actress, she lacked the natural talent to become a truly great one.

Louisa listened to her mother and waited. At twenty-five, she had another episode of being “stage struck” and wrote, “Perhaps it is acting, not writing, I ‘m meant for. Nature must have a vent somehow.” Her plans didn’t work out – she decided that, while she had the skills to be a good amateur actress, she lacked the natural talent to become a truly great one.

Although she gave up the idea of an acting career, Louisa continued to act for fun for most of her life. She even used her performing skills to cheer up wounded soldiers and distract them during painful surgeries when she worked as a Civil War nurse.

After she became a famous author at the age of thirty-five, she still participated in different plays for charity and was famous for her impersonations of Mrs. Jarley, a character from Charles Dickens’s The Old Curiosity Shop.

Henry David Thoreau finds the handkerchief of a fairy

Henry David Thoreau lived in Concord, MA, during the same time Louisa’s family did and was a close friend of the Alcotts. Not only did he delight Louisa, her sisters, and the other town kids with stories about nature and simple living, he also often took them on walks around Walden Pond.

Henry David Thoreau lived in Concord, MA, during the same time Louisa’s family did and was a close friend of the Alcotts. Not only did he delight Louisa, her sisters, and the other town kids with stories about nature and simple living, he also often took them on walks around Walden Pond.

During one such walk, he pointed towards what looked like nothing but thin air and, with an excited voice, asked Louisa if she saw it.

“See what?” Louisa replied.

“Look carefully,” Henry David Thoreau told her.

“I don’t see anything.”

“Look closer.”

“The cobweb?” Louisa asked, confused that such an ordinary thing could make her companion so happy.

“Why, Louisa,” Henry David Thoreau said with a twinkle in his eyes, “that’s not just a cobweb. That’s the handkerchief of a fairy.”

Walks like that were a favorite pastime for Louisa and they became lifelong cherished memories. In her journal she wrote: “Arrowheads and Indian fireplaces sprang from the ground during our walks. Wild birds perched on his shoulder. His fingers seemed to have more wisdom in them than many a scholar’s head.”

When Henry David Thoreau died, Louisa wrote a poem, Thoreau’s Flute, in the memory of her friend and published it anonymously in the popular Atlantic magazine. Many people praised it and thought it had been Ralph Waldo Emerson who wrote it. Louisa joked that, “being a mercenary creature, she liked the $10 she received for it nearly as well as the honor of being ‘a new star’ and ‘a literary celebrity.’”

Louisa May Alcott’s conscience and moods

“Conscience consists of a mind and a soul,” Louisa’s father told his daughters. “The mind is a big, round room and the soul a little creature with wings which lives there. The walls are full of drawers and shelves in which we keep our thoughts and there are goodness, and badness, and all sort of things. The goodness should always be seen and the badness should be locked up.”

In Louisa’s case, “The badness often gets out,” the father told her, “and it is hard work squeezing it down and putting it back. That’s how strong it is.”

Some biographers argue that Louisa was her father’s least favorite child. Some say that Bronson Alcott went so far as to call his wife and Louisa as being “of the Devil” because of their quick temper and “darker looks.” It’s hard to say what Bronson really thought of Louisa but it’s certain that he often called her moody in a way that was meant to point out her weaknesses and teach her to become a better person.

As a child, Louisa tried to keep the room of her mind in order. She wanted to please her parents, especially her mother, and be “good.” Sometimes she shook her head despondently because the room was in disorder and the lock was not strong enough to keep the badness shut up. She compared herself to her sisters and wished she had their calmer, sweet temper.

” My quick tongue is always getting me into trouble,” Louisa wrote in her journal, “and my moodiness makes it hard to be cheerful, when I think how poor we are, how much worry it is to live, and how many things I long to do – I never can. So every day is a battle, and I’m so tired I don’t want to live, only it’s cowardly to die till you have done something.”

Later in life, she become more accepting of her moodiness. She still changed her mind often. Sometimes she called Concord dull, gray, rude, and the last place she wanted to live in; sometimes it was a heavenly place where her mind and body could get the rest they needed. Work was her salvation as often as it was the thing that tormented her. She said she never wished to leave her mother’s side yet wrote that caregiving was a duty that chained her to a galley and stopped her from travelling and doing the things she loved. The list goes on.

She didn’t stop trying to control her moodiness but she did start talking about it with humor, calling it a “failing that gives relish to life.”

Louisa May Alcott’s famous neighbors

How many famous people can a seemingly ordinary town of less than two thousand inhabitants have in the early 1800s? The answer is “a lot” if that town is Concord, MA, which is why Henry James called it “the biggest little place in America.”

How many famous people can a seemingly ordinary town of less than two thousand inhabitants have in the early 1800s? The answer is “a lot” if that town is Concord, MA, which is why Henry James called it “the biggest little place in America.”

Louisa May Alcott spent much of her childhood in Concord. Its well-known artists and innovators were her neighbors and close family friends. Among them there were:

- Ralph Waldo Emerson, author of Self-Reliance;

- Henry David Thoreau, author of Walden;

- Nathaniel Hawthorne, author of The Scarlett Letter;

- William Ellery Channing, transcendentalist poet;

- Daniel Chester French, creator of Abraham Lincoln’s statue in the Lincoln Memorial from Washington D.C.;

- Ephraim Bull, developer of the Concord grape.

When Louisa became famous herself, Concord became the target of many reporters

Born to drown – maybe, maybe not

“This child was born to drown,” a fortuneteller told Louisa’s parents soon after her birth. It was a prediction that came back to Louisa’s mind whenever she traveled by boat or ship.

“This child was born to drown,” a fortuneteller told Louisa’s parents soon after her birth. It was a prediction that came back to Louisa’s mind whenever she traveled by boat or ship.

She first came close to fulfilling it when she was three. She was playing near Frog Pond in the central park of Boston and was saved from drowning by a young black boy. Louisa often joked that it was then that she became an abolitionist.

When she was thirty, Louisa traveled to Washington DC to work as a Civil War nurse. Part of her journey took place by boat. In the short story Hospital Sketches, Louisa talked about the impending “moist death” and her determination not to go down without a fight.

“[I realize that,]” she wrote in her story, “as I was born to be drowned, an eligible opportunity now presents itself; and, having twice escaped a watery grave, the third immersion will certainly extinguish my vital spark. The boat is new, but if it ever intends to blow up, spring a leak, catch afire, or be run into, it will do the deed tonight, because I’m here to fulfill my destiny. With tragic calmness I resign myself […] examine the saving circumference of my hoop, and look about me for any means of deliverance when the moist moment shall arrive; for I’ve no intention of folding my hands and bubbling to death without an energetic splash first.” (Louisa May Alcott – Hospital Sketches)

Louisa survived that journey and the four trips she took across the Atlantic later in life when she visited Europe. It turned out she hadn’t been born to drown. Rather, her end came at the age of fifty-five, from what looked like a stroke or a cerebral hemorrhage.

From murder, revenge, and love triangles to children’s stories

People who read Little Women, Louisa’s most famous book, are either charmed, either bored by it. None are shocked, intrigued, or offended. Its characters are too good and theirs lives too simple to upset anyone.

That’s not the case for Louisa’s earlier stories. Before Little Women, for almost twenty years, Louisa wrote short tales of murder, revenge, suicide, interracial love affairs, and love triangles. She called them potboilers and preferred them to novels because they were fast to write, paid well, and the public loved them.

When her publisher, Thomas Niles, asked her to write Little Women, Louisa was thirty-five and still relatively unknown as an author. She accepted only because she needed the money. She didn’t want to write for kids, especially for girls, because she felt she didn’t knew enough to write an interesting story. She put off work on the novel for months. After trying her publisher’s patience, she went back to her parents’ house and plunged into a “writing vortex.” Six weeks later, Little Women was finished.

Thomas Niles found the book boring but gave it to his young niece who couldn’t put it down. Little Women was published shortly after and sold out its first print within weeks. Its success, a big surprise to both Louisa and Thomas Niles, made Louisa a best-selling and best-earning author. It brought her wealth and fame.

After Little Women, Louisa wrote mainly children’s stories. The couple of times when she published for an older audience, her books received very little praise and didn’t sell well. She returned to writing for young girls and boys even though, at times, she grew tired of providing “moral pap for the young,” as she called it.

Drug addiction

When she was thirty years old, Louisa became sick with typhoid fever while working as an army nurse during the Civil War. The treatment she received contained mercury and damaged her health permanently.

When she was thirty years old, Louisa became sick with typhoid fever while working as an army nurse during the Civil War. The treatment she received contained mercury and damaged her health permanently.

Louisa often said that she had never been sick before the nursing experience, and never healthy after.

After her treatment, she started having strong headaches, joint pain, vertigo, stomach problems, throat pain, and “weak nerves.” At forty-one, her thumb became paralyzed because she used three-pages thick impression paper to write a copy of her novel Work and send it to three different publishers at the same time.

Her worsening health led Louisa to start using strong drugs like opium and morphine. She soon became addicted. Without them, she couldn’t get sleep or relief from pain.

Tragic muse or smoky relic

“She was tall and graceful as a deer,” Belle Moses wrote about Louisa May Alcott. “Her hair was a beautiful glossy chestnut mane, her complexion was clear and full of color, and her blue eyes were deep-set and most expressive.”

“She was tall and graceful as a deer,” Belle Moses wrote about Louisa May Alcott. “Her hair was a beautiful glossy chestnut mane, her complexion was clear and full of color, and her blue eyes were deep-set and most expressive.”

Other biographers described Louisa as beautiful despite her “rather large features.”

At first, Louisa herself liked her looks. When she was a teenager, she wrote, “If I look in my glass, I try to keep down vanity about my long hair, my well-shaped head, and my good nose.”

Age and illness changed that.

After the success of Little Women, fans from all over the country came to visit her. Many were disappointed with her looks. Louisa tells the story of the little Southern girl who came to the Alcotts’ house and, after having waited eagerly hours, broke out crying and “would not be consoled” when she finally saw her idol.

Another group of fans wrote Louisa and asked for her picture. Louisa sent it with the following note: “I send you the last photograph I have – not very good, but you can’t make a Venus out of a tired old lady.” After receiving the picture, the fans and their friends couldn’t hide their disappointment. Louisa sent them another letter and wrote, “I sympathize with your friends on seeing my picture, for I remember I was so upset when I saw Fredericka Bremer, whose books I loved, that my sister Nan and I went into a closet and cried, though we were great girls of sixteen and eighteen.”

At thirty-seven, while on her second visit to Europe, Louisa had her portrait painted by George Healy, whose last commission before that had been Pope Pius IX. George Healy didn’t want money for his painting. Instead, he asked Louisa to give writing and publishing advice to his young daughter who was a young aspiring novelist.

Louisa’s father disliked the portrait because “the flesh was haggard and the features too elongated for a true lifelike likeness.” Louisa agreed.

At fifty-three, Louisa published Jo’s Boys, her last novel. Despite her publisher’s protests, the only illustration in the book was a bas-relief of her head. “Sorry you don’t like the bas-relief,” she wrote to her publisher. “I do. A portrait, if bright and comely, wouldn’t be me, and if like me, would disappoint the children; so we had better let them imagine ‘Aunt Jo young and beautiful, with her hair in two tails down her back’; as the little girl said.” The little girl she referred to was the young Southern reader.

Towards the end of her life, when talking about photographs and portraits of her, Louisa wrote “When I don’t look like the tragic muse, I look like a smoky relic of the Boston fire.”